Hello, storm enthusiasts and curious minds of the natural world! Have you ever watched the news, eyes wide, as reports of cyclones brewing over the ocean surface flash across the screen? These powerful weather phenomena, with their howling winds and torrential rains, are both awe-inspiring and fearsome. But what sets the stage for the birth of a cyclone?

On November 12, 1970, the Bhola cyclone barreled up the Bay of Bengal. Sustained winds of 240 kilometers per hour and a storm surge or flooding raised the sea level to 10.4 meters. The damaging wind and flooding were devastating. The Bhola cyclone is the deadliest tropical cyclone, killing 300,000 to 500,000 people.

Weather encapsulates all the atmospheric conditions in a specific place at a particular time. You can expect the weather to be unpredictable if you live in the mid-latitudes or roughly 35 and 55 degrees north and south latitudes. A bright sunny day in South Dakota, the South Island of New Zealand, or Scotland can suddenly change to overcast and grey and abruptly clear up.

There are many complex global circulation patterns in the atmosphere and the oceans. The Earth is curved and tilted. The amount of incoming solar radiation, or insolation, isn’t the same everywhere. Tropical regions receive two and a half times more energy yearly than the poles. It has to be evened out with the help of atmospheric circulation.

We’re embarking on a thrilling journey into the heart of these atmospheric giants. From the warm waters of the oceans to the complex interplay of atmospheric pressure and wind, we’ll uncover the fascinating process that leads to the formation of cyclones. So, grab your weather maps and join us as we dive deep into the science behind these formidable forces of nature. Are you ready to whirl into the eye of the storm? Let’s set sail into the tempestuous world of cyclones!

How is Cyclone formed?

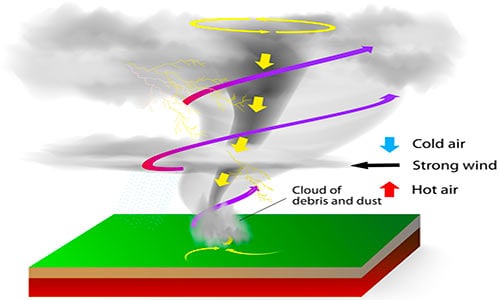

Cyclones form over warm ocean waters near the equator, characterized by low atmospheric pressure, strong winds, and heavy rainfall. Here is a general explanation of how cyclones are formed:

Warm Ocean Waters: Cyclones require warm ocean waters with temperatures typically above 26.5°C (80°F) to provide the necessary energy for their formation. The warm waters evaporate, releasing moisture into the atmosphere.

Moisture and Convection: As the warm ocean water evaporates, it creates a moist and unstable atmosphere. The moisture-laden air rises rapidly due to convection, forming an area of low pressure at the surface.

Coriolis Effect: The rotation of the Earth causes a phenomenon known as the Coriolis effect. This effect deflects the moving air to the right in the Northern Hemisphere and the left in the Southern Hemisphere. It is crucial for the cyclone’s rotation.

Low-Pressure System: The rising warm air creates a region of low atmospheric pressure near the surface. Air from the surrounding areas with higher pressure flows towards this low-pressure region.

Formation of a Tropical Depression: If the low-pressure system becomes more organized and sustains itself for an extended period, it can develop into a tropical depression. The depression is characterized by a closed circulation of winds and maximum sustained winds of up to 61 km/h (38 mph).

Tropical Storm Formation: When the sustained winds in the tropical depression reach speeds between 61 km/h (38 mph) and 119 km/h (74 mph), it is classified as a tropical storm. At this stage, the storm is given a name.

Cyclone Formation: If the tropical storm intensifies and the sustained winds exceed 119 km/h (74 mph), it is classified as a cyclone, hurricane, or typhoon, depending on the region. The storm develops a distinct eye at the center, surrounded by a spiraling band of thunderstorms.

Storm-force winds, torrential rain, massive pressure falls, and storm surges are all produced simultaneously by the most deadly weather. These massive storms are cyclones around the Indian Ocean and the southeast Pacific. Cyclones tend to affect countries like Madagascar, India, and Australia. In the Northwest Pacific, tropical storms are known as typhoons.

There are three basic stages in the life of a tropical cyclone. Its origin or source is the mature and dissipation stages, where it dies out. These occur in a continuous process, not as separate in distinct stages. Each stage may occur more than once during the life cycle. As the cyclone’s strength rises and falls, it may reach land weakened, then return to the sea, where it strengthens again. The formation of a cyclone depends upon the following conditions coinciding.

The warm ocean area has a surface temperature that exceeds 26.5 degrees Celsius over an extended period. It allows warm air to develop above the ocean’s surface. Low-altitude winds are also needed to form a tropical cyclone. As air warms over the ocean, it expands, becomes lighter, and rises. Other local winds blowing to replace the rising air have also warmed and risen.

The rising air contains vast amounts of moisture evaporated from the ocean’s surface. It cools, condensing to form huge clouds about ten kilometers up in the troposphere as it rises. More warm air rushes in and rises, drawn by the draft above. The rising air drafts carry moisture high into the atmosphere, so these clouds eventually become thick and heavy.

Condensation then releases the latent heat energy stored in the water vapor, giving the cyclone more power. It creates a self-sustaining heat cycle. Drawn further upwards by the new release of energy, the clouds can grow to 12-15 kilometers high. The force is created by the Earth’s rotation on a tilted axis.

The Coriolis effect causes rising air currents to spiral around the tropical cyclone’s center. At this stage, the cyclone matures, and the eye of the storm is created. As the air rises and cools, some dense air descends to form that still clear eye as the cyclone rages around it. The eyewall where the wind is strongest behaves like a whirling cylinder.

- Cyclones rotate clockwise in the southern hemisphere and anti-clockwise in the northern.

The lowest air pressure in a tropical cyclone is always found at the center. Also, it is typically 950 millibars or less. The average air pressure at the Earth’s surface is about 1010 millibars. Tropical cyclones have significantly lower air pressure than the air that surrounds them. The bigger the pressure difference, the stronger the wind force.

One of the lowest air pressures ever recorded was 877 millibars. Typhoon Ida hit the Philippines in 1958, where winds reached 300 kilometers an hour. Once formed, the Cyclone’s movement or track follows a pathway away from its source, driven by global wind circulation. The cyclone grows as warm ocean waters feed it with heat and moisture.

Scientific explanation: What are the causes of cyclones? Everything is in place. Converging trade winds meet the warm air with water vapor rising. In the cooling, the air-water vapor condenses into droplets. This state changes from water vapor to liquid and releases latent heat, warming the atmosphere and becoming more buoyant. The air rises even more rapidly and produces more violent thunderclouds. But that’s only the beginning.

Trade winds drawn in at the Earth’s surface arrive on a curved path due to the Earth’s rotation. As the storm grows, more moist, warm air is drawn at the surface. More water vapor condenses into cloud droplets and releases more latent heat. This is how energy is driven into the storm, and the speed of rotation increases. This system is now a tropical storm.

When the surface wind reaches sustained speeds of over 74 miles an hour, the storm is officially a Category 1 hurricane. What’s happening inside the storm-rising currents of warm, moist air from thunderclouds? As the air cools, it becomes denser and falls again. We get this alternating pattern of storm clouds with clear slots in between. It gives us the appearance of spiraling rain bands.

As a hurricane intensifies, it develops a distinctive structure with what looks like a hole in the middle of a swirling mass of clouds. This clear zone in the storm’s center is called the eye, and around it is the eyewall. The eyewall is the most destructive part of the hurricane, containing the most severe thunderstorms and the strongest winds.

Types of cyclone

There are two main types of cyclones: tropical cyclones and temperate cyclones. These cyclones happen several times a year for the region and temperature.

Tropical cyclones: A tropical cyclone is an area of low pressure that forms in tropical regions. They help essentially balance out the temperature across the globe. They take the heat energy from the tropics. The generic term is a tropical cyclone, which can refer to any cyclone with a closed center of circulation globally, like in the Atlantic. We call them hurricanes when they get strong enough to a certain wind speed.

Temperate cyclones: Airmasses are huge atmospheric volumes with particular temperature and humidity characteristics. When two different air masses come into contact, they don’t mix. They push against when a warm air mass meets a cold air mass. The warm air rises since it is lighter at high altitudes. It cools, and the water vapor. It contains condenses. This type of front is called a warm front. It generates nimbostratus clouds, which can result in moderate rain.

On the other hand, a cold air mass catches up with a warm air mass. The cold air slides under the warm air and pushes it upward. As it rises, the warm air cools rapidly. This cold front configuration gives rise to cumulonimbus clouds, which are often associated with heavy precipitation and storms. As air masses move pushed by winds, they directly influence the weather in the regions they pass in this way. They help to circulate heat and humidity in the atmosphere.

Mid-latitude cyclones: The uneven amounts of insolation also cause temperature differences that drive some of the biggest rebalancing efforts. Mid-latitude cyclones are also called wave cyclones or extratropical cyclones. These enormous weather systems span 1000 kilometers or more. A mid-latitude cyclone is a relatively huge circular weather system. It is a relatively smaller, extremely windy tropical storm.

Mid-latitude cyclones can last a week or more, bringing many daily weather changes or severe storms as they travel west to east with westerly winds. These weather systems can form in the mid-latitudes of both hemispheres. In the Northern Hemisphere, mid-latitude cyclones form along the polar front. It is a low-pressure band between two large high-pressure areas in the latitudes below the poles.

- The subtropical high pressure is to the south, and the polar high is to the north.

A battle rages in the skies between the warm, moist air from the tropics and the poles’ cold air. The term “polar front” was first proposed by Norwegian meteorologists Jacob Bjerknes and Halvor Solberg. When an air mass forms over tropical oceans, it will be relatively warmer and more humid than one over northern Canada’s frigid interior. It will be cold and very dry. As they move, they bring their temperatures and moisture with them.

The mid-latitudes get a lot of clashes between air masses. Many storms and precipitation come from when different air masses come together. If the displaced warm air is unstable and has lots of moisture, we’ll get heavy rain from thunderstorms and an advancing wall of cumulonimbus clouds. But when a cold air mass backs off, the warm air mass sees its chance and creeps in, forming a warm front. The warm air can’t displace the denser, colder air near the ground.

The first sign of one is high cirrus clouds, followed by lower and thicker altostratus clouds. Then, still, lower and thicker stratus clouds bring drizzly rain. Air masses bring different weather in their wake and influence locations’ weather conditions as they pass. These winds blow very fast because there’s less friction higher up. A wind blows fast within the upper-air westerlies about 10 kilometers above the Earth. It’s the polar front jet stream, which travels up to 450 kilometers per hour.

As the air converges, rises to form a low-pressure area, and turns into a full-blown mid-latitude cyclone, the colder air mass is denser and moves faster. It won’t be over until the cyclone is wholly cut off from the warm air mass, energy, and moisture source. A storm that starts in the tropical oceans between the Tropic of Cancer and the Tropic of Capricorn can grow to have incredible winds of over 118 kilometers per hour. They go by many names: hurricanes in the Atlantic, typhoons in the Pacific, and cyclones in the Indian Ocean.

How to prepare for a cyclone?

To protect from cyclones, you must follow some advice and safety tips. These can help to reduce the suffering rate. Here are some tips before, during, and after the cyclone.

Safety tips before the cyclone

- Monitor the weather conditions from your local weather station through mainstream and social media.

- Be informed and ensure your place can withstand strong winds and heavy rains. It helps to check roofs for weeks and other parts of your house for damage.

- Have your survival kit ready. It may include first-aid kits, flashlights, cellphones, batteries, whistles, power banks, and other essential items.

- Make sure that there is enough source of drinking water.

- Place pertinent documents and waterproof containers. Clothes should be placed in plastic bags.

- Coordinate with local authorities for possible evacuation if advised to do. So never hesitate to evacuate when evacuating.

- Switch off the primary power source of the house and unplug all electrical devices. Lock all doors and windows.

- Don’t forget to bring money in case of a storm.

Safety tips during the cyclone

- Keep calm and stay indoors continuously.

- Monitor the weather from your local weather station through mainstream and social media.

- If electrical power is down, use a battery-operated transistor radio to check the news.

- Keep away from flooded areas unless you want to catch leptospirosis or fall into a maintenance hole.

- Double-check the weather conditions.

It is important always to be ready for any situation.

We’ve navigated through the warm ocean currents, soared on the updrafts of rising warm air, and felt the pressure drop in the eye of the storm, understanding the incredible forces that come together to create a cyclone. This journey has not only illuminated the raw power of nature but also underscored the importance of preparedness and respect for the might of our planet’s weather systems. We hope this adventure has sparked your curiosity and deepened your appreciation for the complex beauty of Earth’s atmospheric phenomena.

Each cyclone tells a story of energy, movement, and change, offering insights into the interconnectedness of our world. Until our next foray into the wonders of nature, stay curious, stay prepared, and continue to marvel at the forces that shape our weather and climate. Happy exploring, fellow adventurers into the heart of the storm!

More Article:

What Causes A Hurricane To Form?

What Causes A Tornado To Form?

References:

Glossary of Meteorology. “Cyclonic circulation.” American Meteorological Society.

BBC Weather Glossary. “Cyclone.”

“UCAR Glossary — Cyclone.” University Corporation for Atmospheric Research.