Hey there, bird enthusiasts and curious minds! Have you ever found yourself marveling at the incredible agility and speed of hummingbirds as they dart through the air, almost as if they’re performing a magical dance? You’re not alone in your wonder! These tiny aviators are nature’s masterpieces, capable of aerial feats that are nothing short of astonishing.

If you’ve ever watched a hummingbird, they are astounding creatures, flitting around quickly and beating their wings faster, sometimes 70 times per second on average. Some researchers at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Vanderbilt University put their heads together to figure out how this works. How are they able to fly in a very unique and fastest way?

We’re diving into the fascinating world of hummingbirds to uncover the secrets behind their speedy flight. So, buckle up and prepare for a journey that promises to be as enlightening as it is exhilarating. Let’s explore how these remarkable birds manage to fly so fast!

How do hummingbirds fly so fast?

Hummingbirds are ravenous. Eagle can soar and maybe flap once a minute or something if it has to. But then a hummingbird stays where it needs to flap. However, often it is a second. They eat half their body weight daily and need a lot of energy. Their metabolism is outrageous. It’s the fastest metabolism of any creature or any animal. They’re fueled by flower nectar.

Hummingbirds are known for their exceptional flying abilities and ability to fly at incredibly fast speeds. Here are several factors that contribute to their high-speed flight:

Rapid Wingbeat: Hummingbirds can rapidly beat their wings, with an average rate of 50 to 80 beats per second, and some species even exceed 200 beats per second. This rapid wingbeat generates lift, allowing them to hover in mid-air and maneuver swiftly.

Wing Shape and Flexibility: Hummingbirds have long, narrow wings with a unique shape resembling a figure-eight. This shape creates a whirlwind effect, generating lift and reducing drag. Additionally, their wings are highly flexible, allowing for precise control and maneuverability during flight.

Enhanced Muscle Power: Hummingbirds possess strong flight muscles relative to their body size. Their pectoral muscles, responsible for wing movement, are exceptionally developed, enabling powerful and rapid wingbeats.

High Metabolic Rate: Hummingbirds have an extremely high metabolic rate, allowing them to convert food into energy efficiently. This high metabolic rate supports the rapid wingbeat and sustained flight required for their fast and agile flight capabilities.

Hovering and Forward Flight: Hummingbirds have the unique ability to hover in mid-air, thanks to their rapid wing beat, wing flexibility, and precise control. They can also fly forward, backward, and sideways with excellent maneuverability, enhancing their agility and speed.

Feeding Adaptations: Hummingbirds’ fast flight is closely related to their feeding habits. They rely on nectar as their primary energy source, and their ability to hover and fly quickly allows them to access nectar-rich flowers and compete with other birds for food resources.

Aerodynamic Adaptations: Hummingbirds have various aerodynamic adaptations that minimize drag and enhance flight efficiency. These adaptations include streamlined bodies, reduced body weight, and small body size, all contributing to their fast and agile flight.

Hummingbirds have an upstroke and a downstroke when they’re beating their wings. During the downstroke, tiny air vortices formed around the wings combined into one giant vortex. They can create an area of low pressure underneath the wing air, then flood to equalize. The pressure generating the lift is needed to maintain the hover. So they also have another trick up their sleeve, though.

Researchers think of motion capture. They painted non-toxic and essential points. They painted on a ruby-throated hummingbird and a female and painted dots on their wings. Then, they got a 3D model by using a fluid dynamics model. As you said, it was an average mystery at 70, but it can go up to 200 flaps per second! It is astonishing! Only comparable with insects. So dragonflies, mosquitoes, and houseflies can do this. They can hover and then sharply move from one side to another, back and forth, and up and down.

So hummingbirds generate positive lift on the downward stroke and negative lift on the upward stroke. They’re doing both at the same time. Birds would not be generating that exam the upward stroke exactly.

- They generate at least 30% more force when they generate the negative lift. They filmed that bird using a 1,000 frames per second camera, which generated exciting footage.

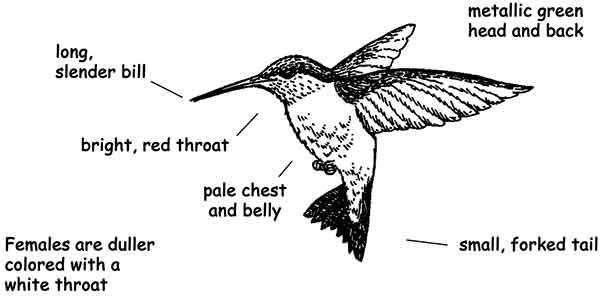

Physical structure

Flying birds tend to have the same wing anatomy as the human arm. Their bones differ in proportion and flexibility depending on the bird’s size. Also, lifestyles like albatross and hummingbird have the same wing bones. But even if they were the same size, their wings would look very different.

Albatrosses are set up to soar for long distances without flapping, so the parts of their wings are very elongated. But hummingbirds have to move their wing constantly. So, they have more length in their upper wing bones, especially the humerus, which connects to the shoulder. The way these bones move is anatomically unique.

Birds flap their wings up and down, gaining all their lifting power on the downstroke. But how many words twist the bones and their shoulders? So they can stroke forward and backward and gain lift from both directions.

- Super-slow-motion studies of hummingbird flight show that their wings make little horizontal figure eights, generating about 75% of the lift on the downstroke and another 25% on the upstroke, allowing the little guys to hover indefinitely.

In this way, hummingbirds fly more like insects than birds. It takes a lot of energy to keep your heart beating and wings flapping at such speed. For this, hummingbirds have another secret weapon: their metabolism. They do occasionally eat insects and nectar.

Nectar is straight-up sugar; when an almond bird eats, its muscles can immediately burn. Whatever sugars it ingests, avoid the energy-draining process of first converting sugar into fat so that it goes right from the blood into muscle tissue. As a result, hummingbirds can’t store fat. Instead, they burn sugar so fast.

Why do hummingbirds fly so fast?

Scientists at UC Berkeley brought hummingbirds into the lab for a closer view. First, the wild birds had to be trained, one at a time, to feed on an artificial flower filled with sugar water. Hummingbird wings buzz like helicopter blades too fast for the naked eye to see. But by recording them with a high-speed camera at 1000 frames, a second scientist can see the individual wing movements. They can see how hovering works.

Most birds flap their wings up and down to fly. But hummingbirds move their wings backward and forward in a figure-eight movement, like oars. This generates lift during the upstroke and the downstroke. It helps hummingbirds stay stable instead of bobbing up and down.

But how would a hummingbird respond when the weather gets rough? The scientists moved the hummingbird into a wind tunnel and began recording to find out. The wind is coming from the right side of the cage up to 20 miles per hour. The hummingbird must fly into the wind to get the sugar water. They turn and twist their body in the airflow direction while using their wings for control and their tail like a rudder to stay steady. Even rain can’t stop the hummingbird from feeding.

See how the bird shakes off drops of water from its body, like a wet dog? The birds can’t afford to eat. They have to consume their weight in nectar every day to survive. The flowers need them, too. As they eat, hummingbirds spread pollen from plant to plant. It’s a symbiosis, a two-way street between a bird and a flower. These tiny flying machines have evolved ways to hold up their end of the bargain: rain, wind, or shine.

Why do hummingbirds hover?

Two researchers from the University of British Columbia claim to have found a glitch in the hummingbird hover system. The researchers found that altering a hummingbird’s visual stimuli while it attempts to feed causes the bird to falter in flight. The hummingbirds were put into a laboratory flight arena. They hovered around a plastic feeder before a surface that projected images. When still images were projected, the birds had no visible response. Moving images, however, seemed to trip their game up.

A rotating spiral, for example, caused the hummingbirds to drift backward repeatedly as they tried to contact the feeder. A reboot was triggered when the bird’s beak broke contact with the feeder. The bird would return to its original hover position to get tripped up again by the same images.

The researchers suggest quote – “the hummingbirds’ visual motion detection network can over-ride even a critical behavior like feeding.” These findings could open the door to more research on other exciting ways flying birds use visual information.

Hummingbirds flap their wings around 50 times a second, allowing them to feed in place. It’s like treading water, but in mid-air and at high speed. It takes a lot of energy. If they don’t consume double their body weight in calories daily, they won’t survive.

Most birds take cover in the rain, but hummers do the opposite. The cooler temperatures increase their metabolic rate, and every drop of nectar is a matter of life or death. As the storm clears, other males horns in on his territory.

Hummingbirds fly about 30 miles per hour, but they’ll do looping displays when they’re in courtship display. Each species does a different display. It’s the male. It displays the female and says, “Here I’m.” So they’ll do that before they mate. She will pick whichever male she likes, up to 63 miles per hour. They also fly when flying over and migrating from the United States over the Gulf.

They fly as high as they can fly, over waves over the waves, or as they fly 500 feet. Also, they’re tiny, the ruby-throated ‘X that are migrating from the north. It’ll help engineers figure out new models of very effective aerodynamics for planes and jets in the future. It will aid them in better creating and designing efficient flying machines. The hummingbirds are fascinating to watch when they fly.

It’s truly remarkable how these tiny birds exhibit such power and grace, all thanks to their unique anatomical features and tireless energy. We hope this exploration has not only satisfied your curiosity but also deepened your appreciation for these feathered wonders. The next time you spot a hummingbird zipping through your garden, take a moment to marvel at the extraordinary capabilities packed into such a small package. Thank you for joining us on this high-speed adventure, and keep your eyes on the skies for more marvels of nature!

Read More:

How is Cheetah The Fastest Animal?

References:

Clark, C. J.; Dudley, “Flight costs of long, sexually selected tails in hummingbirds.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Ridgely RS, Greenfield PG. The Birds of Ecuador, Field Guide (1 ed.). Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8721-7.

Suarez, R. K. “Hummingbird flight: Sustaining the highest mass-specific metabolic rates among vertebrates.” Experientia. 48 (6): 565–70.

Vigors, Nicholas Aylward. “Observations on the natural affinities that connect the orders and families of birds.” Transactions of the Linnean Society of London.

Table of Contents