Hello, ocean explorers and nature enthusiasts! Have you ever stood at the edge of the sea, watching the waves roll in and out, and wondered what mysterious forces lie beneath, driving the vast and varied currents of our oceans? The movement of ocean currents is a captivating phenomenon, integral to the health of our planet, influencing climate, marine life, and even human activities.

The oceans cover two-thirds of the Earth’s surface. That’s hundreds of times heavier than the entire atmosphere. Earth’s oceans are connected by a vast, global conveyor belt of moving water. A planetary circulatory system transports heat, nutrients, and even animals around the globe.

This circulatory system keeps us alive. Earth’s network of moving ocean water keeps the planet healthy. It powers a huge part of Earth’s weather and climate and shapes ecosystems. Ocean currents have even influenced the history of human civilization. The engine of this entire global ocean current? Salt, some sunlight, and a little wind power it.

We’re diving into the depths of the ocean to uncover the secrets of what drives these powerful currents. From the warming rays of the sun to the spinning of the Earth itself, we’ll explore the complex interplay of temperature, salinity, wind, and the Coriolis effect that keeps our oceans in perpetual motion. Whether you’re an avid sailor, a conservationist, or simply someone with a thirst for knowledge, this journey promises to immerse you in the wonders of our blue planet. So, let’s set sail on this aquatic adventure and navigate the currents that connect our world.

What Drives Ocean Currents?

Ocean currents are driven by various factors, including wind, temperature, salinity, the Earth’s rotation, and the ocean floor’s topography. Here are the main drivers of ocean currents:

Wind: Surface ocean currents, known as surface currents, are primarily driven by winds. The friction between the moving air and the ocean’s surface transfers momentum to the water, causing it to move in the same direction as the wind. Wind patterns, such as the trade winds and westerlies, play a significant role in shaping major ocean currents.

Coriolis Effect: The rotation of the Earth influences the direction of ocean currents through the Coriolis effect. In the Northern Hemisphere, the Coriolis effect causes moving water to be deflected to the right, while in the Southern Hemisphere, it deflects to the left. This effect contributes to the formation of circular patterns in large-scale ocean currents.

Temperature and Density: Differences in water temperature and density drive ocean currents. Warm water is less dense than cold water, so it rises and flows toward colder regions, creating a circulation pattern known as thermohaline circulation. These deep ocean currents, called density currents, are important for global redistributing heat.

Salinity: Variations in seawater salinity can influence ocean currents. When water becomes saltier due to evaporation or other factors, it becomes denser and sinks, driving the movement of deeper currents. Areas of high evaporation, such as near the equator, can contribute to the formation of dense, salty water masses that sink and flow toward lower latitudes.

Tides: Tidal currents are driven by the gravitational pull of the Moon and the Sun. Tidal forces cause water to move in a rhythmic pattern, resulting in the ebb and flow of tides. These tidal currents can interact with other ocean currents and influence local water movement.

Underwater Topography: The shape and features of the ocean floor, including seamounts, ridges, and canyons, can influence the direction and strength of ocean currents. These features can deflect or channel currents, creating complex flow patterns.

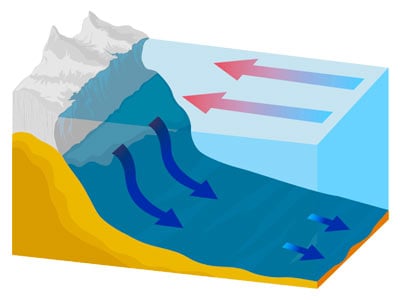

Ocean currents form due to cold water close to the surface sinking and swapping places with warmer water. This cyclical motion causes vertical currents. It is the air that moves all that water around ocean currents. The oceans aren’t separate things. A huge ocean current, the ocean conveyor, ties them together.

The conveyor belt is a long-moving loop of ocean currents that drives water, nutrients, plants, and animals worldwide. It is a mixture of warm, shallow currents with colder, deeper currents underneath. It drives huge amounts of water; some sections have a current of around 10 Sverdrups. Sverdrup is the special unit that ocean scientists use to talk about the vast quantities of water going around in the oceans.

- One Sverdrup is a current of 1 million cubic meters passing by per second!

The circulation is also huge in terms of time. It can take one bit of water a thousand years to make one loop around the swirling global path. So what makes this huge conveyor run?

The first thing you need to know about how ocean currents work is. There are lots of ways that ocean currents work. Near the surface, ocean currents are controlled mainly through the wind. Like blowing across the top of water pulls the water along with it. Surface currents are influenced by tides, the rotation of the Earth, and even the land’s shape. But more than 9/10ths of the ocean’s water is pulled by a deeper force: density.

- Hot water is less dense than cold water. Because its molecules are a bit farther apart, you can’t fit as much water in the same volume. So, a volume of hot water weighs slightly less than the same volume of cold water. Cold water sinks below the warmer water.

- The blue water is much colder than the red water. Like cold ocean water, the layer of cold water sink beneath the red, warm water. When it speeds up the force of the rising and falling water densities creating a current, it is one of the major driving forces of Earth’s deep ocean circulation: colder waters sinking and warmer waters rising.

The dissolved salt ions fill the unused space between water molecules in salt water. It means more mass in a given volume of saltwater than freshwater. So saltier water is denser than fresher water. Temperature and saltiness are crucial to how the ocean conveyor circulates.

What is thermohaline circulation? Thermo refers to temperature, and haline to saltiness. As water evaporates, cold water on the ocean’s surface gets saltier in high latitudes. When sea ice forms, it pulls pure water out of the sea and leaves salt behind, making the ocean water saltier.

The heat from the sun eventually warms the cold water at the surface, where evaporation makes the water saltier. This warm salted water is carried northwards by large, powerful wind-driven ocean currents like the Gulf Stream, up the U.S. east coast, then into the North Atlantic region. Here, it releases heat into the atmosphere and warms Western Europe. This water becomes cold and dense again and sinks into the deep ocean, continuing the cycle.

Cold, salty water formation in the North Atlantic acts as a pump, driving nearly half of Earth’s deep ocean water circulation. This section of the Great Ocean conveyor is called the Atlantic Meridional overturning circulation or AMOC.

The heat released by the AMOC has huge climate effects, bringing moderate rains to Europe and about a million power plants worth of heat to some parts of the planet! Consider that London in the UK is roughly the same latitude as Calgary, Canada, but Calgary is way colder! That’s in part due to the heating Europe gets from the AMOC.

How do global ocean currents drive?

The global conveyor belt is a series of ocean currents that snake worldwide. They are called haline thermal currents because they result from changes in temperature and salinity. These changes in temperature and salinity create currents in the ocean.

The conveyor belt begins on the sea’s surface near the pole of the North Atlantic. The Arctic temperature chills the water. It also gets saltier because the salt does not freeze when ice forms in the ocean and is left behind in the surrounding water.

Surface water moves in to replace the sinking water, creating a current that moves south towards the equator and the ends of Africa and South America. The current now travels around the edge of Antarctica, where the water cools and sinks again.

As it does in the North Atlantic thus, the conveyor belt gets recharged. Two sections split off the conveyor and move northward as it moves around Antarctica. One section moves into the Indian Ocean, the other into the Pacific Ocean.

The two branches of the current warm and rise as they travel northward, then loop back southward and westward. The non-warm surface waters continue circulating the globe. Eventually, return to the North Atlantic, where the cycle begins again. The conveyor belt moves much slower than wind-driven or tidal currents.

The importance of ocean currents drive

Ocean currents are significant. They control weather patterns around the world. Researchers have argued that a big part of Europe’s political and economic power over the last several millennia has come from the moderate climate conditions brought by the AMOC.

If northern Europe was as cold as its latitude suggests, the Romans might not have gone Empire as far. The Vikings don’t Viking everywhere. The English, Dutch, and Spanish would have spent more time huddling beside the fireplace instead of colonizing every country on the map.

All this climate change is pretty essential for ocean circulation. Climate scientists think an interruption of the AMOC in the past may have triggered a sudden, extremely cold spike in the Northern Hemisphere climate. Also, there’s a reason they call it global warming: pretty much everywhere is heating up.

Recent studies showed that the ocean currents in the North Atlantic are slowing down. It means that the circulation in the ocean is causing fish populations to decline, sea levels to rise, and a dramatic change in global climates. Scientists hypothesized that increasing atmospheric temperatures and decreasing salinity in the ocean are significant factors behind this change.

We’ve explored the sun’s warmth, the saltiness of seawater, the push of the winds, and the spin of the Earth, all converging to create the currents that drive the ocean’s vast circulatory system. This journey has not only deepened our understanding of the marine environment but also highlighted its critical role in regulating the Earth’s climate and sustaining life both in the sea and on land.

As we part ways, let’s carry with us a renewed sense of awe for the complexity and beauty of our planet’s oceans, along with a commitment to preserving this vital resource. Thank you for joining me on this enlightening exploration of what drives ocean currents. Until our next adventure into the mysteries of the natural world, keep your curiosity as boundless as the sea and continue to seek out the wonders that lie beneath the waves.

More Articles:

How Do Ocean Currents Affect The Weather?

How Does The Moon Affect Tides?

References:

NOAA, “What is a current?”. Ocean Service Noaa. National Ocean Service.

“Massive Southern Ocean current discovered.” ScienceDaily.

Yasushi Fukamachi, Stephen Rintoul; et al. “Strong export of Antarctic Bottom Water east of the Kerguelen plateau.” Nature Geoscience.

National Ocean Service. “Surface Ocean Currents.” National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.