Sea turtles are some of the most magnificent and wondrous animals alive today. These organisms represent an ancient and complex evolutionary history spanning hundreds of millions of years. Modern sea turtles are part of a subgroup within the larger order known as the Testudines. It includes all surviving animals, such as Turtles, Tortoises, or Terrapins.

In 1887, a scientist in Germany announced the discovery of a fossil animal that was new to science. The thing was a turtle. It had a shell with a flat plastron on the bottom fused to a carapace on top. So it had all the requirements for what makes an official turtle. But this was not only a whole new genus and species of turtle. It was also the oldest turtle ever found at the time. This discovery sparked a debate over turtles that lasted more than a century.

How does the turtle get its shell?

The evolution and development of the turtle shell is a fascinating topic that scientists have been studying for many years. The exact origins of the turtle shell are still a subject of ongoing research. Still, several hypotheses and evidence-based theories shed light on how turtles acquired their unique protective structure. Here are some key points:

Ancestral Reptile Ribs: Turtles belong to the reptile group, and their ancestors likely had a ribcage similar to other reptiles. Fossil evidence suggests that the turtle shell evolved from modifying the ancestral reptile’s ribcage.

Broadened Ribs: One hypothesis proposes that over time, the ribs of early turtle ancestors broadened and elongated, providing increased protection to the body. These broadened ribs may have initially offered some defense against predators or other environmental threats.

Plastron Development: Another significant aspect of the turtle shell is the plastron, which forms the shell’s ventral (underside) portion. The development of the plastron is thought to be associated with the fusion or expansion of other skeletal elements, such as the clavicles (collarbones) and gastralia (abdominal ribs).

Carapace Formation: The dorsal (upper) part of the turtle shell, known as the carapace, likely formed through a combination of processes. It may have resulted from the growth of bony plates called osteoderms that fused with the broadened ribs and the expansion and fusion of other bones in the back and spine.

Protection and Adaptation: The evolution of the turtle shell is believed to have provided significant benefits in terms of protection against predators, environmental hazards, and possibly changes in habitat. The shell offers a strong and rigid structure that helps shield the turtle’s vital organs and provides a degree of camouflage.

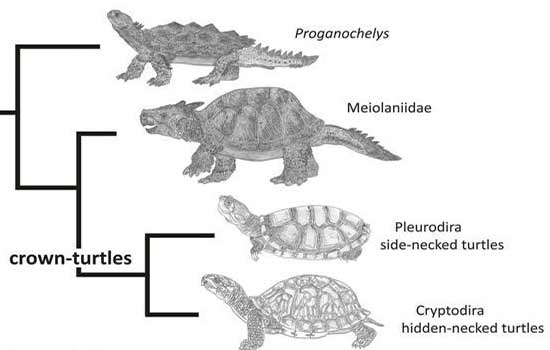

Where did turtles come from? What lineage gave rise to these weird reptiles with beaks for mouths and retractable necks? How did the turtle get its shell? The answers would eventually cause scientists to rethink the entire history of reptile evolution. The German turtle that started all this was called Proganochelys. It means “early shell,” which lived about 210 million years ago, in the late Triassic Period.

It was about a meter long, about half the length of the largest species alive today. But unlike modern turtles, Proganochelys hadn’t yet developed the ability to retract its head under its shell. The fact that its shell was found intact was beneficial. That made it easy to identify this animal as a true turtle. But at the same time, it left a lot of open questions about how that shell evolved, and why it resembled modern turtles in some ways but not in others.

So the discovery of this creature kicked off a debate about which major taxonomic group, or clade, of reptile turtles, belonged to. Most reptiles fall under the clade known as eureptilia, or “true reptiles.” This includes stuff like lizards, snakes, dinosaurs, and birds. But there’s also parareptilia, or “side reptiles.” These are some of the earliest reptiles. All of which are now extinct, like the spiky-cheeked procolophonids and the mesosaurs. They were probably the first aquatic reptiles.

Which clade you put turtles in depends on where you think its shell came from. In the late 19th century, most paleontologists thought turtles belonged in the clade we now call parareptilia. They shared the same basic skull structure as other para reptiles.

- By the late 1940s, this theory became even more specific, suggesting that turtles were related to a particular group of extinct parareptiles called pareiasaurs.

These are sometimes called the “ugliest reptiles.” For example, they lived in the Permian Period around 260 million years ago. It was covered in a layer of hardened scutes. Likewise, a later pareiasaur called Anthodon had more developed bony plates that formed a layer of armor like a turtle’s shell. So it’s not hard to see why many paleontologists thought pareiasaurs were closely related to turtles and maybe even their direct ancestors.

The idea was that over time, the scutes found in pareiasaurs could have fused into a solid protective layer, eventually combining with the ribs to form a shell. But, how scientists are! No one likes a good, rigorous, centuries-long argument more than they do! Enter the developmental biologists. They study how living things grow throughout their lives.

- Starting in the late 1920s, some of these biologists studied the embryonic growth of modern turtles. They found that, as turtles develop, bones that function as lower ribs widen and fuse, forming the plastron.

Then another set of bones up top, the “normal” ribs, do the same, widening and fusing to form the carapace. So these scientists proposed that turtle evolution took a similar path, with widened ribs forming first and the shell later. By the 1990s, the idea had taken off. It was the opposite of what the paleontologists proposed that the shell on top evolved from scutes. That fused before combining with the ribs below. If the developmental biologists were right, turtles wouldn’t be para reptiles. They’d be much more similar to eureptiles.

So, both sides had some evidence to support their cases. But it was hard to resolve the debate without more and older fossils. Then, in 2008, researchers found one in China. It was shaped like a turtle but only had the bottom shell, the plastron. Also, it didn’t have a carapace. It was a shell-less turtle! They called it Odontochelys. It dates to about 220 million years ago, around 10 million years before Proganochelys from Germany.

It had a plastron without a carapace, which was pretty strong evidence for the developmental biologists’ hypothesis that it evolved first. But there was more. Unlike all other known turtles, Odontochelys had teeth. Its name means “toothed turtle.” Those teeth looked nothing like pareiasaur teeth. Pareiasaurs had teeth with little cusps on them, like human molars. But this turtle’s teeth were more like pegs.

So it looked like this ancient turtle didn’t belong in the para reptiles group. It was a eureptile. Eventually, this would be supported by several other genetic studies in the last few decades. It compared the turtle genome with other reptiles and placed turtles in a subgroup of eureptilia. But while all that was happening, more species were added to the turtle family tree.

Why do turtles have shells?

In 2010, the discovery of Odontochelys led researchers to reexamine another ancient species called Eunotosaurus. It lived about 260 million years ago in Africa, long before Proganochelys and the previously found Odontochelys. The first fossil of this species was originally found back in 1892. But most experts at the time didn’t think it was a turtle ancestor because it didn’t have a shell. But it did have broad, flat ribs. Modern paleontologists noticed that it bore more than a passing resemblance to Odontochelys.

Finally, in 2015, researchers discovered another early turtle in Germany called Pappochelys, or “grandfather turtle.” It lived about 240 million years ago and had wide ribs, with a set of bones below them that were partially fused but not to the point that they formed a plastron.

So old grandpa turtle seemed to mark a transitional stage between Eunotosaurus, its wider ribs, and Odontochelys, its complete plastron. Together, these discoveries helped fill out the timeline of turtle evolution. It became clear that the first step in the evolution of turtle shells was forming wider ribs. But there was still the question of why.

Why did turtles acquire these weirdly wide ribs in the first place? What purpose did they serve? Why did they eventually develop into shells? Well, in 2016, paleontologists again took a closer look at Eunotosaurus. It is now considered the oldest of the turtle ancestors. Most of us think turtles are adapted for life in the water, with webbed feet or flippers. But Eunotosaurus seemed to have a lot of adaptations for burrowing through the dirt.

Its head was shaped basically like a shovel. Its front legs were stronger than its rear legs, and it had giant claws that would have been great for digging. So, the evidence pointed to life as a borrower. This could help explain why it had those wide ribs and where turtle shells came from.

Researchers proposed that wider ribs would’ve been useful as an anchor when Eunotosaurus Eunotosaurus was digging with its front legs. Wider ribs provide a more stabilized trunk. It would have made it easier for the turtle to keep its body in one place while digging. Other burrowing animals, like anteaters, have similar adaptations. The problem is that having wide ribs with such short legs makes walking hard. Or at least walking quickly.

Turtles are so famously slow that their giant ribs make it hard to swing their little legs forward. So, ancestral turtles needed extra-wide ribs for digging, which slowed them down. Now they needed more protection. That’s when the ribs started to fuse into a plastron, which eventually became an entire protective shell.

Over time, the evolutionary purpose of the turtle’s shell changed from digging to protection, and turtles, as we know them, became a thing. Of course, none of this is fully resolved. In theory, it makes sense for wider ribs to have evolved for digging, but that’s based on what we’ve seen in one species right now. We still need a lot more evidence.

The turtles’ exact place among the eureptiles isn’t settled either. Many researchers think they’re more closely related to a clade that includes animals like crocodiles and birds. But others argue that they’re closer to a different group, including lizards and snakes.

Hopefully, it won’t take another 130 years to answer that debate. But either way, we now know that the turtles’ branch isn’t turtles down on the Tree of life. It’s stacked with a diverse array of reptilian characters. Some of which have no shells, others of which have partial shells. Others still sport the full, beautiful shells and famously slow gaits today.

More Articles:

How The Squids Lost Their Shell?

Why Did Dinosaurs Get So Huge?

References:

Turtle Taxonomy Working Group (2017). Turtles of the World: Annotated Checklist and Atlas of Taxonomy, Synonymy, Distribution, and Conservation Status. Chelonian Research Monographs. 7 (8th ed.).

Hutchinson, J. (1996). “Introduction to Testudines: The Turtles.” University of California Museum of Paleontology.

“Species numbers (as of Aug 2020)”. Reptile Database.

Simoons, Frederick J. (1991). Food in China: A Cultural and Historical Inquiry.

Burton, Maurice; Burton, Robert (2002). International Wildlife Encyclopedia.

Ernst, C. H.; Lovich, J. E. (2009). Turtles of the United States and Canada.

Fergus, Charles (2007). Turtles: Wild Guide. Wild Guide. Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books.