Horses evolved in North America. They were North American species for millions of years until they became extinct 12,000 years ago. Then horses were brought back to North America by Europeans. But they are still the same lineage of horses that evolved millions of years ago in North America. The original horse project aims to understand the origin and evolutionary history of horses in North America and worldwide.

So far, scientists have collected more than 500 remains from horses that lived across the Northern Hemisphere. They recover DNA from all of these and compare the DNA sequences.

They discovered that horses moved across the Bering land bridge, which connected North America and Asia during glacial periods when the sea level was much lower than today. It exposed a land bridge connecting these two continents. Whenever there was a land bridge, horses moved from North America into Siberia and back into North America.

How did horses come to North America?

Around 11,000 years ago, horses disappeared from North America due to climate change and overhunting by early human populations. However, horses were reintroduced to North America much later through the arrival of European explorers and settlers. Here’s a general timeline of how horses came back to North America:

Extinction and Absence: By the end of the Pleistocene epoch, approximately 11,000 years ago, horses went extinct in North America. It is believed that changing climate conditions and the overhunting of large mammals by early human populations contributed to their disappearance from the continent.

Reintroduction by Europeans: European explorers and settlers reintroduced horses to North America. The Spanish conquistadors brought horses, specifically domesticated horses of European and Arabian descent, during their expeditions to the New World, starting in the late 15th century. These horses quickly spread and established feral populations.

Feral Horse Populations: As the introduced horses escaped or were abandoned by their European owners, they formed feral populations in various regions of North America. Over time, these populations adapted to the local environments and developed into unique groups, such as the Mustangs in the western United States.

Expansion and Wild Horse Management: Feral horse populations in North America continued to expand and thrive. Today, wild horse populations exist in various regions, particularly in the western parts of the United States and Canada. These populations are managed through various programs to balance their impact on ecosystems and protect their welfare.

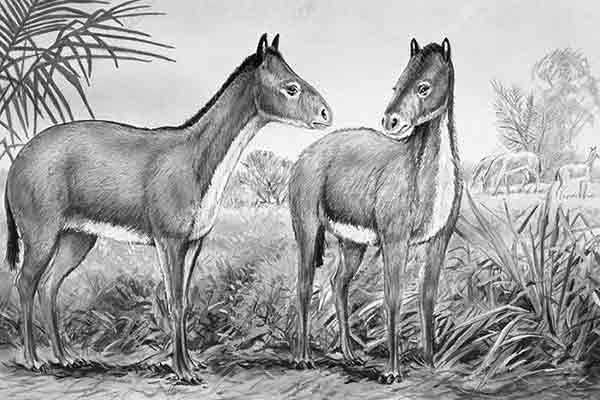

It was 55 million years ago in North America. The continent is draped in swampy cypress trees and humid broadleaf forests. Like the hoofed carnivore Mesonyx, Bizarre predators lurk in the undergrowth, ready to catch an animal called Eohippus.

Eohippus may be small, half a meter tall, but it’s also fast and well-adapted to its environment. It runs on padded toes, each capped with a cute Lil hoof, perfect for a quick getaway on the soft forest floor. But the future has significant changes in store for little Eohippus.

The climate is about to get cooler and drier, and soon the landscape of North America will become unrecognizable. Trees will give way to vast carpets of grass. Mesonyx and other forest hunters will go extinct, and powerful, new, pack-hunting predators will evolve. The Descendents of Eohippus will undergo dramatic changes to adapt to life on these newly forming plains.

They’ll grow to be over 30 times their size. They’ll change their diet entirely. Also, they’ll all start running on one big toe. In time, these animals will become so successful that they’ll spread worldwide to Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa. But in their native range of North America, they’ll vanish for 10,000 years until another strange mammal brings them back.

At the start of the Eocene Epoch, the world was in the clutches of the Paleocene-Eocene, thermal maximum, and warm, damp forests covered the land from pole to pole. This environment gave rise to the first perissodactyls, hoofed mammals with an odd number of toes. Today they include rhinos, tapirs, and horses.

One of the first perissodactyls we know of is Hyracotherium. A small ungulate whose first discovered fossils in England were named for their resemblance to the rock hyrax. Many different Hyracotherium-like animals, known as hyracotheres, were widespread throughout the Northern Hemisphere. One of them, found only in North America, was Eohippus or “dawn horse.” American paleontologist O.C. Marsh named it. He found the first complete animal fossil in New Mexico in 1876.

It was about the size of a dog, around 35 centimeters at the shoulder. Like other hyracotheres, it had short, low-crowned teeth that were good for browsing on leaves in the dense forest. Eohippus also had feet unlike any animal is alive today, with toes each capped with separate hooves: four on its front feet and three on its hind feet. It gave rise to the most successful family of Perissodactyls of all time, the Equidae, which includes the modern horse.

At the height of its diversity, the Equid family would include more than a dozen genera that roamed the northern hemisphere. However, only one genus remains, Equus, including modern horses, donkeys, and zebras.

Thanks to an abundance of fossils found throughout North America. We can reconstruct much of the horse family tree, from the tiny, browsing, multi-toed Eohippus at its roots to one of the crowning branches. That includes the extensive, grazing, single-toed Equus.

The story of horse evolution is about constant adaptation and radiation in response to North America’s climate changes. All of these adaptations were driven by the appearance of grasslands, which weren’t widespread in North America when Eohippus was around.

Evolution of horses by Earth timeline

About 49 million years ago, the climate became more relaxed and drier in the mid-Eocene. By the late Eocene, the Thermal Maximum was history, and North America’s dense forests began to give way to a mosaic of dry grasslands. It was in this patchwork environment that a descendant of Eohippus first appeared.

Mesohippus began to show up about 38 million years ago, first described by O. C. Marsh in 1875. In concise order, at least geologically speaking, Mesohippus’s lineage quickly diversified into another genus, Miohippus, within about 3 or 4 million years.

So, Mesohippus and Miohippus roamed the continent together at the start of the Oligocene. But they were both different from Eohippus in some important ways, showing they were starting to adapt to North America’s changing landscape. For one thing, they both had more molars than Eohippus did. Their teeth had higher crests for grinding more fibrous, abrasive food, like grass.

Both were also slightly larger than Eohippus and with longer legs. Mesohippus weighed around 23 kilograms, while Miohippus averaged about twice that. Both had lost their fourth front toe, while their middle toe had grown larger and had more weight. By the mid-Oligocene, the smaller Mesohippus had disappeared. But the larger Miohippus survived and radiated into many different species that flourished in the following epoch, the Miocene.

By this time, the swamps, forests, and grasslands mosaic wasn’t a mosaic. The forests and marshes had given way to wide stretches of dry, open prairie. One of the most important likely descendants of Miohippus was an equid that was even better adapted to life on Parahippus. Paleontologists have learned a lot about one particular species of this horse, Parahippus leonensis. Thanks to a quarry in Florida, where nearly 90 specimens have been found.

It first appeared in the fossil record about 23 million years ago, and its adaptations to prairie life went further than having pointy molars. Namely, it was the first early horse to be a true hypsodont. That means its teeth were long and kept erupting out of the gums as they wore down to reveal a new chewing surface.

This proved to be a massive advantage for living on the plains. Because if you’re going to make a living by eating grass, which is abrasive, you need large teeth that can withstand a lot of wear. This adaptation helped Parahippus and its descendants, take full advantage of North America’s fastest-growing niche.

About 17 million years ago, the fossil record shows that a new, distinct genus evolved from the Parahippus lineage, Merychippus. Merychippus is another meaningful benchmark in horse evolution because it’s the first equine. Equines are the subfamily of equids that includes modern horses. Like Merychippus, they all have important traits that earlier horses lacked.

For one thing, Merychippus was a lot bigger. It stood about a meter tall, the height of a small pony, and had the long head we’d now call horse-like. Even more so than its ancestors, its legs were especially well adapted to running on hard ground. It stood tip-toe, with all its weight on three toes supported by springy ligaments. Its leg bones were also longer, and the bones in the foreleg were fused, making them stronger and able to withstand more force.

With the help of these adaptations, equines like Merychippus grew larger than forest-dwelling horses, reaching up to 450 kilograms. Being so big probably helped them deal with large Miocene predators, like saber-toothed barbourofelids. But their size also puts much more stress on their legs and toes. That is until yet another new adaptation appeared: Several descendants of Merychippus became monodactyls, meaning they had only one toe.

Like Dinohippus, which appeared about 10 million years ago, some horses in this genus still had three toes. But others only had one! Counterintuitively enough, having only one large toe reduced the stress caused by the horse’s weight. Horses began relying more on their ligaments over time to compensate for the lost stability. So, as they became increasingly adapted to their grassy new environment, equines thrived throughout the Miocene.

Then, the Pliocene Epoch opened about 4 million years ago. One of the single-toed groups of equines finally gave rise to Equus, the genus of the modern horse. We don’t know which one it was exactly. But Dinohippus seems to be the monodactyl most closely related to the horses we know today. Now, the oldest-known species of Equus is Equus simplicidens.

It appeared about 4 million years ago and has been found from Florida to the Hagerman Fossil Beds in Idaho. It was about the size of a modern horse, with similar teeth, a long face and neck, fully fused leg bones, and a well-developed “stay mechanism.” Horses use these to lock their legs in place, an adaption for spending most of their time on their feet. Unlike their predecessors, species of Equus didn’t stay confined to North America.

About 3 million years ago, they crossed into South America as part of the Great American Biotic Interchange. After about a half-million years, they crossed the Bering Strait land bridge to spread into Asia, Europe, and Africa. All three-toed horses and most other monodactyls died out during this time. Then, about 10,000 years ago, most of North America’s large mammals, including Equus, went extinct at the end of the Pleistocene.

There’s a big healthy scientific debate about what caused this extinction event, but it’s safe to say that it was probably a combination of factors. The end of the last ice age brought many major changes to the continent, like habitat and vegetation patterns. Bison populations began to grow and spread, competing with horses for food. The fossil record shows that horses’ ranges were shrinking and that some horses themselves may have gotten smaller to help deal with the lack of resources. Then, humans showed up.

Horses as domestic animals in North America

Scientists have found evidence that these early humans hunted horses, probably putting more pressure on struggling animals. But, the horses that had migrated out of North America survived the extinction on other continents. Over in Asia, horses traversed the grasslands of the Eurasian Steppes. About 6,000 years ago, humans realized that horses could be pretty helpful.

Like members of the Botai culture in ancient Kazakhstan, people began to domesticate the Equus lineage survivors. All modern horses worldwide are descendants of domesticated horses from this region. Over the next 6,000 years, horses shaped the course of human history. They proved to be a game-changer for everything from hunting and agriculture to war and transportation.

Humans, in turn, shaped horses, selectively breeding them to grow even larger, faster, and in my opinion, even more beautiful. Then, in the late 1400s, Spanish settlers put their horses on ships and brought them across the Atlantic. Much of America was still covered in those open grasslands that horses were so well suited for, and it didn’t take long for them to take over their former range a second time.

The first known feral horses escaped Mexico City around 1550. More escaped from ranches in New Mexico in the 1600s. Native Americans began to capture and ride the horses, spreading them further across the continent.

Horses have become one of the most numerous and widespread mammals. The continent had significantly changed since Eohippus first picked its way through vast, humid forests. But today, millions of domestic horses live worldwide, including 67,000 wild horses. That is back to roaming their native plains members of that second, successful wave of horses that took over North America.

Is the horses a native North American species?

Hundreds, maybe thousands of incredibly well-preserved remains from these horses help better understand how horses responded to past periods of climate change. When horses went extinct 12,000 years ago, they were locally extinct but not globally extinct.

When Europeans brought them back to North America several hundred years ago, they reintroduced a native species to the North American continent. Horses were returned to North America several hundred years ago. It is related to the horses that disappeared from North America 12,000 years ago. This is the same lineage as the horse. They are fantastic, diverse, and beautiful creatures who deserve to live here.

More Articles:

How Do Horses Run So Fast Speed?

References:

Singer, Ben (May 2005). A brief history of the horse in America. Canadian Geographic Magazine.

Ancient American Horses. Joseph Leidy Online Exhibit. Academy of Natural Sciences of Drexel University.

Ancient Horse (Equus cf. E. complicatus). Academy of Natural Sciences.

Table of Contents